Introduction

The rapier is thought to be the precursor to the modern fencing foil. It evolved from the arming sword to the side sword before changes in armor led to the blade becoming longer and thinner, prioritizing thrusting over cutting.[1] The long and thin rapiers were primarily civilian weapons, intended for self-defense and dueling. Rapiers built for war were also used, as this article from Arms & Armor showcases. However, the vast majority of available source material deals with the long and thin, thrust-oriented civilian rapier.

The complex hilt was developed to better protect the hands and was also incorporated into other sword designs, such as the saber and Scottish broadsword. A parrying dagger was sometimes used alongside the rapier so that a fighter could parry (ward off) the opponent’s rapier while striking at the opening created. Other off-hand weapons like shields and cloaks were also used. The two largest rapier systems were the Italian, which focused on linear movement, and the Spanish, which emphasized circular movements.[2]

An example of a German rapier.

Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Public Domain.

This video gives a brief introduction to the rapier.

A breakdown of rapier anatomy.

Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, edited by Nicholas Allen. Public Domain.

Hilt Evolution

The hilt evolved from that of the side sword, eventually developing into a complex basket around the hand called a “swept hilt”.

An example of a "swept hilt" rapier.

Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Public Domain.

Over time, the gaps in the guard were filled in until the guard became a solid shell called a “cup hilt.”

An example of a "cup-hilt" rapier.

Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Public Domain.

Both swept hilts and cup hilts are subtypes of a “complex hilt,” which is a broad term indicating that the guard is more elaborate than a simple cruciform crossguard.

The Parrying Dagger

The parrying dagger was designed for parrying thrusts and typically had a wide crossguard to make catching the blade easier. There were several different types; some later models incorporated improved hand protection. The rapier and dagger combination was used by both civilian and military factions all over Europe.[3]

A civilian cup-hilted rapier, and it's accompanying parrying dagger.

Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Public Domain.

An example of a rapier and dagger used together.

Courtesy of Lil Shepherd.

Sources

Italian

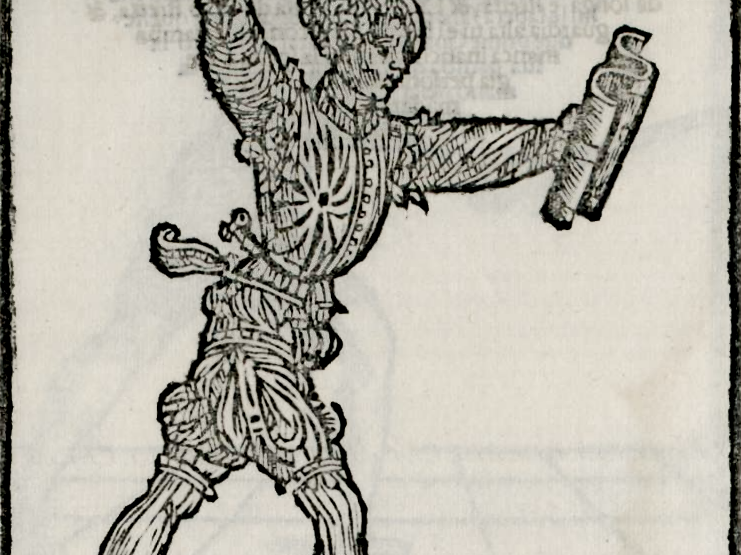

Nicoletto Giganti (1606-1608): Giganti was an Italian soldier and fencing master around the turn of the 17th century. In 1606, Giganti published a treatise on the use of the rapier both as a standalone weapon and as used with the dagger. In 1608, he published a second volume that covers the same weapons as the first with the addition of rapier and buckler, rapier and cloak, rapier and shield, single dagger, and mixed weapon encounters.

Salvator Fabris (1606): Fabris was a 16th- and 17th-century Italian knight and fencing master who traveled extensively all over Europe throughout his life. He published his most important work, Sienza e Pratica d’Arme ("Science and Practice of Arms"), while serving as the chief rapier instructor to the court of Christianus IV, King of Denmark and Duke Johan Frederik's cousin. The importance of Fabris' work can hardly be overstated. Versions of his treatise were reprinted for over a hundred years and translated into German at least four times as well as into French and Latin. He is almost universally praised by later masters and fencing historians, and through the influence of his students and their students (most notably Hans Wilhelm Schöffer), he became the dominant figure in German fencing throughout the 17th century and into the 18th. A complete translation of Fabris’ work can be found here.

Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli (1610): Capo Ferro published a broad rapier treatise that deals with the rapier both by itself and with the dagger. Though this treatise is highly praised by modern fencing historians, it is neither comprehensive nor particularly innovative and does not seem to have been influential in its own time. Nick Thomas, instructor and co-founder of the Academy of Historical Fencing, has published a companion workbook that is designed to be used alongside Capo Ferro’s treatise.

Francesco Fernando Alfieri (1638-1641): Alfieri was a prolific author publishing a treatise on the banner, then a text on fencing, before penning an extremely popular text on the rapier. This latter text was reprinted in 1646 then received a new edition in 1653 which not only includes the entirety of the 1640 edition, but which also adds a concluding section on the spadone. Like other Italian masters before him, Alfieri emphasizes displacing the enemy’s blade by taking advantage of minute changes in tempo and angle in order to gain leverage. A complete translation of his work can be found here.

Flemish

Gérard Thibault d'Anvers (1630): Thibault was a 17th-century Dutch fencing master and author of the 1628 rapier manual Academie de l'Espée, one of the most detailed and elaborate sources ever written on fencing. His work is presented in two parts; the first introduces his techniques and describes their use and application. The second book was incomplete at the time of his death but appears to show how to counter other rapier systems as well as other contemporary weapons like shields, longswords, and firearms.

Spanish

Jerónimo Sánchez de Carranza (1569): Carranza is one of the most influential fencing masters in history owing to the fact that he founded a new system of rapier fencing based on science and geometry which he called la Verdadera Destreza ("The True Skill") in contrast to the esgrima vulgar ("vulgar fencing") taught by other masters. He was immortalized in Spanish poetry and literature, and his name became synonymous with skill in fencing. Carranza's treatise was reprinted several times over the following century, and his successor succeeded in virtually eliminating the other schools of Iberian fencing in favor of Carranza's teachings.

Luis Pacheco de Narvaez (1600-1625): The greatest student of Jerónimo Sánchez de Carranza, Narvaez was arguably the most prolific fencing author in history. He published his first treatise on the Destreza soon after his master's death, quickly followed by at least eight other printed fencing manuals, including a revised edition of Carranza's own work. Later in life, he devoted great energy to undermining Carranza's legacy and to exposing and correcting perceived flaws in his system. This broke the Destreza tradition into two competing camps, the Carrancistas and Pachequistas, a schism that was never mended. A complete scan of his work can be found here. Scholars can also find translations of the first and third parts of Narvaez’s latest work criticizing the Destreza system.

German

Joachim Meyer (1560-1570): Meyer was a German Freifechter (a member of a fencing guild) and fencing master. He was the last major figure in the tradition of the German grandmaster Johannes Liechtenauer. His work on rapier represents one of the few rapier systems in existence not influenced by Fabris. His rapier system is designed to be used with the lighter, single-hand swords spreading north from Iberian and Italian lands and seems to be a hybrid creation, integrating both the core teachings of the 15th-century Liechtenauer tradition as well as components that are characteristic of the various regional Mediterranean fencing systems.

Michael Hundt (1611): Hundt’s rapier treatise is deep and detailed, discussing fundamental movements, cut and thrust attacks, and the use of offhand weapons like the parrying dagger or buckler. He even covers how to fight against multiple opponents and mixed weapons like firearms and saber.

Demonstration

A demonstration of basic rapier techniques with the rapier alone

A demonstration of basic rapier techniques with rapier and dagger

An exhibition of rapier sparring with rapier alone.

An example of a rapier and dagger fight

Martian Fabian’s introduction to rapier series presents foundational rapier techniques designed for beginner fencers.

Equipment

I have made an extensive list of recommended rapier equipment for beginners in HEMA.

Works Cited

Footnotes

[1] Blood and Iron HEMA, What Exactly *Is* A Rapier? - Showcasing HEMA, video, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vpi9gHT7LSc.

[2] “What Exactly *is* a Rapier?”

[3] "Ridolfo Capo Ferro Da Cagli ~ Wiktenauer ~☞ Insquequo Omnes Gratuiti Fiant", Wiktenauer.Com, 2020, http://wiktenauer.com/wiki/Ridolfo_Capo_Ferro_da_Cagli.

Citations

Blood and Iron HEMA. What Exactly *Is* A Rapier? - Showcasing HEMA. Video, 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vpi9gHT7LSc.

"Ridolfo Capo Ferro Da Cagli ~ Wiktenauer ~☞ Insquequo Omnes Gratuiti Fiant". Wiktenauer.Com, 2020. http://wiktenauer.com/wiki/Ridolfo_Capo_Ferro_da_Cagli.

Written by Nicholas Allen, founder and former head instructor of the VCU HEMA club.

Edited by Kiana Shurkin, xKDF

Historical sources fact-checked by Michael Chidester, Editor-in-Chief of Wiktenauer